by Frank E Earp

A few weeks ago I received an e:mail from one of my many contacts urging me to vote for the Major Oak in a competition for ‘The European Tree of the Year’. The Major Oak with its associations to the Robin Hood story, is of course the most famous tree in Sherwood Forest, – and perhaps the most famous oak tree in Britain.

The European Tree of the Year: As the name suggests, the competition, which began in 2011, is an annual pan-European popularity contest for trees across the continent, – it has been described as the Eurovision for trees. Competing trees are judged for their cultural value to the local, national and even international community. From an initial start of only 5 participating countries, this year’s competition has seen entrants from 14 European states including England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

Celebrity trees from across each of the competing countries are first nominated for the national heat of the competition. The resulting national finalist then go ‘head to head’ to be ‘crowned’ by public vote with the title of European Tree of the Year. All of the nominees for the title have their names and details added to ‘The European Trail of Trees, further enforcing their celebrity status.

Disappointingly, the Major Oak did not win the competition despite votes coming from fans as far away as the U.S.A. The Major Oak received 9,941 of the total of 185,000 votes cast and was soundly beaten into sixth place. The winner, an Estonian oak tree know as ‘The Football Tree’, received 59,836 votes just short of 32% of total votes cast. So, what makes this Estonian oak, – which by the way although a mature tree, is a mere sapling compared to Sherwood’s mighty giant, – so special and valued to the community? The fact is that the tree appears to have been judged more on its novelty status than any cultural heritage or history, for it stands in the middle of a football-pitch. Before 1951 the tree stood on the edge of a small sports ground in the town of Orissaare. When the facility was expanded, the tree which was protected, ended up in the middle of the stadium. Space dictated that it was necessary to layout a football pitch around the tree. The tree however takes an active part in games played on the pitch, with players from both sides allowed by local rules to use it has an extra player and deflect balls off of its’ trunk. Before its honoured role in the game of football, the oak was already a symbol of national resistance. Legend has it that Russian forces under Stalin tried to uproot the tree using two tractors but failed when the cables kept breaking. Locals proudly point out the marks left on the tree’s trunk from this attempted destruction.

Scotland’s entrant to this years competition was a 100 year old Scots pine which stands close to the waters edge at the Scottish Wildlife Trust’s, Loch of the Lowes reserve near Dunkeld, Perthshire. Known as Lady’s Tree, the pine’s claim to fame is that it has, for nearly a quarter of a century, been the chosen nesting site for the country’s most famous osprey, a bird known as Lady. Lady’s Tree came 9th in the competition with 4,193 votes.

The entrant for Wales, also a Scots pine twice the age of Lady’s Tree, came 10th with 1,548 votes. This solitary tree, appropriately referred to as the Lonely Tree was once a familiar landmark high on the top of a hill above the town of Llanfyllin, Powys. In April 2014 the tree blew over in high winds and to help promote their efforts to save the tree, the good folk of the town entered it into the competition.

Oak Trees in European culture: It is not surprising that in a competition in which trees are judged for their cultural value and importance, that we should find that three of the fourteen contestants are oak trees. What is a surprise is the fact that there were not more. The oak tree has held a place of high esteem in most European cultures for thousands of years. Across Europe it has always been associated with the chief deity of the many and various pantheons of pagan gods and goddesses, particularly those who’s attributes are represented by thunder and lightning, – Zeus, Jupiter and Thor. In Britain the Iron Age Druids, – who’s very name derives from the Latin for ‘oak knower’ – conducted their ceremonies in oak groves. Famously, the most sacred plant of the Druids is the mistletoe, particularly that which is found growing on an oak tree. In folklore, the legendary Merlin, who is probably based on an actual Druid, has strong associations with the oak.

The history of the birth of Christianity in both Britain and Continental Europe is littered with incidents of the cutting down of pagan sacred oak trees. In France, the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne ordered the destruction of the pagan sacred oak groves. The Christianization of the Germanic peoples was said to have begun when, in 723 A.D., a Christian missionary named Winfrid cut-down an oak tree sacred to the god Thor.

Like the tree its self, the pagan veneration of the oak was so deep rooted that the early Christian Church found it hard to entirely extinguish. As with other pagan imagery, the oak leaf and acorn became incorporated into church architecture in the form of the ‘green man’ or more correctly the ‘foliate head’, as a symbol of the wild and lustful side of human nature.

Heart of Oak: There are far to many examples of the oak trees significance in British and European folklore and culture to give further space to in this article, but it is safe to say that the oak’s importance in these aspects can not be over emphasized. However, leaving all this aside, the oak has always been prized for its strength and beauty and for the value its’ timber. Of all the countries of the U.K. it is England that is perhaps most associated with oak trees, – and for good reason. One might say that it is a tree that both helped build and protect a nation. It was oak trees which were chosen as the preferred timber to provided the great roof beams of Anglo/Saxon halls, Norman castles, great houses, cathedrals and parish churches all over the land. The most famous role of the oak in history is however, that of providing the ‘wooden walls’ which once protected England and the rest of these isles from the threat of foreign invasion. The wooden walls are of course the great warships of the Royal Navy, like Nelson’s Flagship The Victory. Nowhere is the sentiment of the wooden walls better reflected than in the patriotic song and official march of the Royal Navy, ‘Heart of Oak’ The image of the ‘mighty oak’ has become one of England’s national symbols and the great oaks of Sherwood a proud symbol of Nottinghamshire.

Hail, hallow’d oaks:

Hail, British-born, who, last of British race,

Hold your primeval rights by Nature’s charter.

‘Caractacus’ William Mason 1724 – 1797.

Major Hayman Rooke: It is impossible to write about the ‘Great Oaks of Sherwood’ without first mentioning one man, Hayman Rooke. Little is written about Rooke’s early life, however, it is known that he was born in London on the 23rd February 1723 and was christened one month later at the church of St. Martin’s-in-the-Field, Westminster. After following an unremarkable career in the Royal Artillery and having achieved the rank of major, he retired to Mansfield in Nottinghamshire around 1780. Rooke took-up residence at Woodhouse Place at what is now the corner of Leeming Lane South and Mansfield Road and seems to have settled very quickly into a life as a ‘Country Gentleman’ and Antiquarian (Archaeologist). Just how and when he acquired his passion for ‘antiquities’ is unknown, but Rooke had already contributed a number of articles to the journal ‘Archaeologia’ between 1776 and 1796 whilst still serving in the army. Although he took an active interest in ancient sites across the Country, Rooke is best known for his pioneering work in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

As well as his passion for archaeology, Rooke took a deep interest in both meteorology and natural history. A particularly favourite interest was the venerable old oak trees growing all around him in Sherwood Forest. In 1790 he published a book entitled ‘Description or Sketches of remarkable Oaks in Welbeck Park’ and nine years later a pamphlet with the descriptive title of ‘A sketch of the ancient and present state of Sherwood Forest’. Rooke, like most antiquarians of the day was an excellent artist and draughtsman and consequently both books are full of lavish illustrations of all the most notable trees including: The Porters, The Greendale Oak The Duke’s Walking-stick and The Seven Sisters.

Affectionately known locally as the Major, Hayman Rooke died at the age of 83 on the 18th September 1806 and was buried with much acclaim in the chancel, – a place of great honour, – of St. Edmund’s church Mansfield Woodhouse.

Oak with three names: According to legend, one of the Major’s (Hayman Rooke), favourite haunts was a “….beautiful wood or rather grove” known as Birchland, on the Duke of Portland’s Welbeck estate. The Major himself describes the wood as consisting of over 10,000 oaks intermixed with birch trees and covering an area of around 1,800 acres. Of all the oaks in Birchland, there was one special tree to which the Major was drawn. This was an ancient oak known as the Cockpit Tree from the fact that caged cockerels where kept insides its great hollow trunk prior to their participation in the once popular sport of ‘Cock-fighting’. It is said that the Major was often seen to take his morning brake beneath the trees’ spreading boughs. Here he would rest, eat his picnic lunch or write -up his notes. So frequent were his visits to the tree locals began to referrer to it as ‘The Major’s Oak’ and then, simply The Major Oak. Charming as this legend might be it is not entirely true. The fact is that although first referred to as The Cockpit Oak, the tree now known as The Major Oak was also called The Queen Oak or Queen’s Oak throughout the 19th century. Sorting fact from fiction a more likely sequence of events is that the tree’s official or actual name was the Queen or Queen’s Oak and in popular parlance was given the more local nick-name Cockpit Oak due to its associations with the sport of Cock-fighting. Perhaps the Major did take his ease beneath the boughs of this great tree, but the more likely reason for its current name is less prosaic. The fact that the tree was introduced and made popular to a wider audience in his book on the Welbeck Oaks. However, although he gives both an illustration and description of the tree in his work, he does not refer to it by any name. We can imagine then, that those readers of the book wishing see the tree for themselves would turn up in Birchland and amongst its 10,000 oaks and ask the locals “Which one is the Major’s Oak?” The tree is easier to find these days. Birchland is now a part of the Sherwood Forest Country Park and the modern visitor needs only to follow the signs from the Visitors Centre near Edwinstowe.

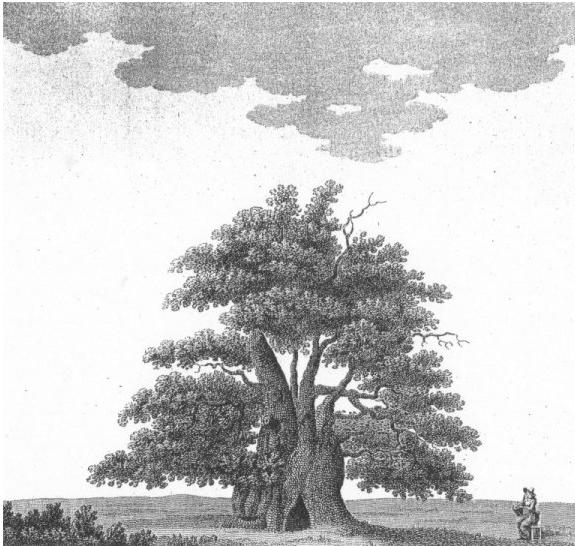

The Major Oak: The first written reference to the oak tree now known as The Major Oak, comes from the pen of the antiquarian Major Hayman Rooke, from whom the tree takes its’ name. There has been many thousands of words written about this tree since the Major’s day, but such is the value of his report that it is worth repeating here in full: “On the north side of the great riding is a most curious antient oak, which, before the depredations made by time on its venerable trunk, might almost have vied with the celebrated Cowthorpe oak. for size. It measures, near the ground, 34′ 4” in circumference; at one yard, 27′ 4”; at two yards, 31′ 9”. The trunk, which is wonderfully distorted, plainly appears to have been much larger; and the parts from whence large pieces have fallen off are distinguishable; the inside is decayed and hollowed out by age, which, with the assistance of the axe, might be made wide enough to admit a carriage through it. I think no one can behold this majestic ruin without pronouncing it to be of very remote antiquity; and might venture to say, that it cannot be much less than a thousand years old”.

One thing is certain about this account, we can learn as much from its omissions as we can its inclusions. It will be noticed that Rooke begins by introducing the Major Oak as ‘a curious antient (ancient) oak’ and gives neither the tree’s vulgar name, the Cockpit Oak or its’ more likely name The Queen Oak. The accompanying illustration also simply has the title ‘An Ancient Oak in Birchland Wood’. With one other exception, all of the other trees in the book are referenced by name and their illustrations appropriately labelled. Did Rooke not know the trees’ name or was it purposefully omitted?

The Major Oak is so famous today that we might have expected it to have had first place in Rooke’s work and for the account to contain the most information. However, this is not the case. The honour of being the first tree mentioned in the book is given to a magnificently tall and straight oak appropriately known as ‘The Duke’s Walking Stick’. The greatest amount of text is given-over to a tree called the Greendale Oak which appears to have been the most famous tree on the Duke’s estate. Although clearly a reference to a venerable old oak, why did Rooke include a description of what seems at the time to be an obscure tree?

‘Description or Sketches of remarkable Oaks in Welbeck Park’, – first published in 1790, – was not intended to appeal to a mass audience. It is a survey of the trees on the Duke of Portland’s estate and was written and paid for by subscription. As the title page, dedications and list of subscribers, (sponsors including the Duke himself) indicate, the book was intended to be read by the aristocracy, gentry and other distinguished members of society. Bearing in mind the intended audience, Rooke seems to have included the Major Oak rather for its great age, size and unique appearance. All this is very cleverly done in his direct comparison in the text with the ‘Cowthorpe Oak’. Aside from the fact that the tree was in Rooke’s time, the most famous oak tree in Britain, why did Rooke make this comparison and where did Rooke learn of the Cowthorpe Oak? The answer to the first question will become apparent when we look at the Cowthorpe Oak in detail. As to the source of Rooke’s information, knowing Rooke’s passion for Sherwood Forest and its great oaks, there is but one possible answer, John Evelyn’s ‘Sylva’.

John Evelyn’s Sylva: Sylva, with the full title of ‘A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty’s Dominions’, was a book that Rooke and his patron, the Duke of Portland would have been familiar with. Rooke’s own books were inspired by, if not directly influenced by this prestigious record of the trees of Britain. Sylva comes from the Latin word for forest and in this case referrers to silviculture, – the general care and maintenance of trees and forests. The work was first presented to the Royal Society in 1662, by one of its founder members the diarist John Evelyn, as a ‘paper’. Two years later, in 1664, at the behest of several Commissioners of the Royal Navy, it was granted a Royal Charter and published as the first ever volume on silviculture in the English language. From this date until 1825 there follow successive editions, the last five being published under the editorship of Dr Alexander Hunter.

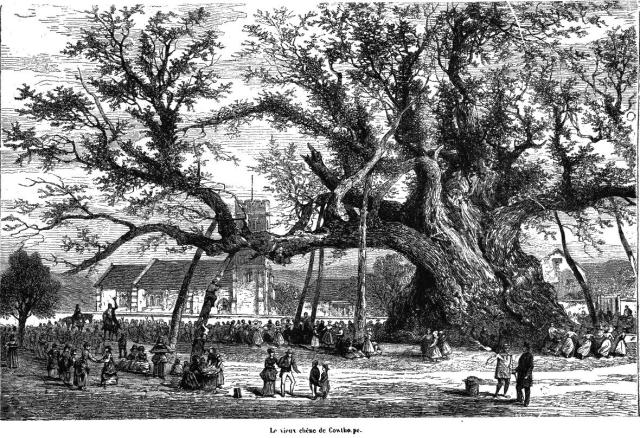

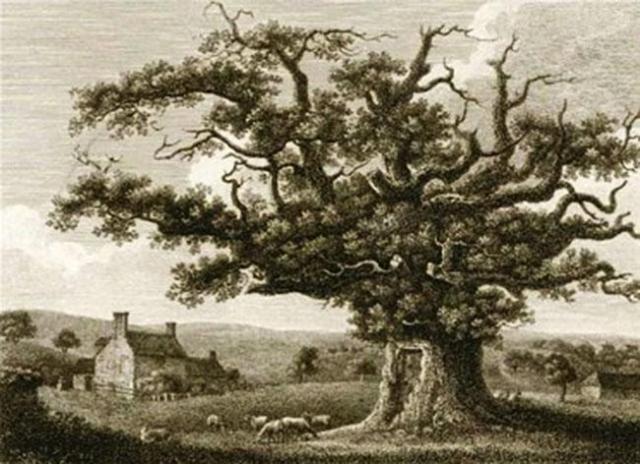

The Cowthorpe Oak: Cowthorpe is a small rural village in the Harrogate district of North Yorkshire around 14 miles from York. The village has but one claim to fame, it was once the home of the greatest and most famous oak tree in Britain. The tree, which was considered to be completely dead in1950, has been estimated to have been around 1,800 years old. Compare this to the estimated age of the Major Oak of between 800 and 1,000 years old. In 1776, writing in his first edition of ‘Evelyn’s Sylva’ Hunter says of the Cowthorpe Oak: “When compared to this, all other trees are but children of the forest”. Hunter’s full description of this truly gargantuan tree makes it nearly twice the size of the Major Oak: “The dimensions are almost incredible. Within three feet of the ground it measures sixteen yards [48′], and close by the ground twenty-six yards [78′]. Its height, in its present ruinous state (1776), is almost eighty-five feet, and its principal limb extends sixteen yards [48′] from the bole. Throughout the whole tree the foliage is extremely thin, so that the anatomy of the ancient branches may be distinctly seen in the height of summer”. The tree is believed to have been in full vigour around 1700 and to have occupied a site of close-on half an acre.

They say that a picture paints a thousand words and certainly this is true of the of the Victorian image of the Cowthorpe Oak reproduced here. Although not the earliest image of the tree, this engraving, first published in the ‘Graphic’ in 1872, shows not only the trees’ amazing size, but its popularity and the truly vast crowds of visitors it once attracted. By this date the tree had already been a popular attraction for over 100 years.

I believe that in making the comparison with the Cowthorpe Oak, Rooke was flattering his patron, – the Duke of Portland, – by drawing his attention to the oak on his estate. He was in fact saying something like; “Look at this my lord. You too have a great oak like the Cowthorpe tree on your land”. I further believe that by not mentioning the tree by name, Rooke cleverly infers that he is responsible for its discovery. Certainly, following the publication of Rooke’s account, the obscure Queen Oak starts it journey to becoming the popular attraction it is today. The fact that the tree is now known as the Major Oak gives full credit to Rooke for the trees popularity.

Two Trees: Who ever entered the Major Oak into this year’s European Tree of the Year competition may have been somewhat technically cheating. Latest scientific opinion tells us that The Major Oak is in fact two oak trees and not one. What is even more amazing is the fact that the two may even be of a different species of oak tree making The Major Oak a unique high-bread. I have it on good authority, – ‘Robin Hood’ himself, a.k.a. Dr Tony Rotherham, that acorns and leafs on one side of the tree are distinctly different from those on the other. It would seem that between 800 and 1,000 years ago, on the spot where The Major Oak now stands, two acorns germinated side by side. As the young saplings grew their branches were close enough to touch each other and by a natural process known as ‘inosculation’ they fussed together. Underground, the same process occurred with the roots of the young trees and by the time that the trunks had grow sufficient to bridged the gap between the pair, they too fussed together. The rest as they say is history but the product of this inosculation is with us today in the form of the mighty Major Oak.

The union of the branches of two or more trees through the process of inosculation is not uncommon, especially where trees of the same genus are growing in close proximity, such as orchards and woods. Even branches of isolated trees will sometimes fuse and become one where gravity or deformity of growth have forced them together. However for two trees of a different but related species to grow together is rare, but when it does happen it produces spectacular results.

The Oak and the Ash: One of these natural unions of two trees, sometimes known as ‘husband and wife trees’ or marriage trees, is described by Rooke in his account of what he referrers to ‘as a fine grove of large oaks’, on the west side of the lake in Welbeck Park. Here he says, are trees of between 12′ and 22′ in circumference: “One of these trees is worthy of notice, being a singular ‘lusus naturae’ [play on nature] which represents an ash growing out of the bottom of a large oak, to which it adheres to the height of about 6′; it there separates, and leaves a space of near three feet in height; here, as if unwilling to be disunited, it stretches out an arm, or little protuberance, to coalesce again with the fostering Oak. Circumference near the ground, taking in both trees, 36′ feet; at one yard, 18′ 9” circumference of the oak only at two yards, 15′ 4”; the ash at two yards, 6′ in circumference; height of the oak 92’”.

A Question of Age: Everyone knows that the easiest way of determine the age of any tree is to cut it down and to count the number of annual growth rings contained within the trunk. Thankfully there is a less destructive method available, simply measure the circumference of the tree at a point of around 5′ from ground level. Because of the special place oak trees have in the culture of the areas in which they grow and the fact that oaks have been deliberately cultivated for many hundreds of years, their growth patten has been widely studied. From these many observations a comparison table of the average diameter of trees of different ages growing in similar conditions has been developed.

Given the right conditions, acorns germinate very quickly. There then follows a rapid period of growth for the first 80 to 120 year where the tree puts on both hight and bulk. At around 80 years old the average oak is around 6′ 7” in circumference and by 120 years of age the tree will have reached a circumference of around 9′ 6”. At this age on, growth begins to slow down. By the time a tree has reached a circumference of just over 22′ it is estimated to be around 500 years old.

What then of the forest giants like the Major Oak? From 900 and 1,000 years old an oak tree will have reached a circumference of between 30′ 11” to 32′ 11”. Rooke gives two measurements for the circumference of the Major Oak; at the height of one yard 27′ 4”, which gives an age of around 800 years and at two yards 31′ 9” equalling an age of around 1,000 years. However, there are other factors to take into account when considering the age of the Major Oak. Rooke tells us that there was evidence in his day that the tree had once been much larger in girth. Could this add extra years to the trees age? If we except the idea that the Major Oak is the product of two saplings grown together as one, how does this effect the estimate of the overall age? I’ll leave it for the reader to ponder on and for the experts to decide.

Oldest Tree in Europe: Until its declared death in 1950, with its massive girth of over 48′ and estimated age of around 1,800 years, the Cowthorpe Oak in Yorkshire was reckoned to be the oldest oak tree in Europe. With this tree now gone, where does this leave the Major Oak in the ranking of Europe’s ancient trees? Disappointingly not in first place. That honour now belongs to a tree in the German village of Nöbdenitz. The tree, simply known by locals as ‘The Thousand Year Tree, is around 40’ in circumference. Like its fellow ancient oaks, its trunk is hollow throughout and is held together by iron bands. Badly damaged by a storm in 1819 the tree is now clinging onto life nourished by only one living root.

Oldest Tree in Britain: If the Major Oak is not the oldest oak in Europe, then the reader might ask ‘surely it is the oldest oak tree in Britain?’ However, the answer once again is no! According to the Guinness Book of Records that title belongs to the Bowthorpe Oak, a tree close to Bowthorpe Park Farm near the Lincolnshire village of Manthorpe. The tree was measured in 1804 and found to have a girth of 37′. Allowing for the additional 206 years of intervening growth, the tree can be estimated to be well over 1,000 years old.

Thor’s Oaks?: It can not be failed to be noticed that two of Britain’s greatest oak trees take their names from locations ending with ‘thorpe’. In such cases where thorpe occurs as a place name element, it indicates a Scandinavian (Viking) settlements dating from the 10th century. Both of these trees are are isolated specimens and are not associated with woods or oak groves. The Cowthorpe tree stands in a field close to the parish church, whilst the Bowthorpe tree is in a field close to a farm once the site of a manor house. The attendant manorial chapel was considered important enough to be acquired by Sempringham Priory in 1226. Knowing these fact and considering the great importance of the oak tree in Norse pagan mythology, could it be that these ancient trees are the direct descendants of trees once sacred to the god Thor?

Hollow Oaks: Perhaps the most recognisable and distinguishing feature of all of the venerable old oak trees where ever they are found growing, is the fact that they are all hollow. This is a process the tree has no control over. Like humans infected by a virus in old age, these trees have succumbed to one of the tiniest of living organisms, a fungal infection. Fungal spores enter the tree through cracks and crevices in the bark and, through a process of rot and decay, the fungus begins to ‘eat the tree form the inside out’. There is no one specific fungus that can be blamed for this decay. Fungal diseases which cause this form of rot are collectively known as sap or heart rots. As well as rotting the core of the tree’s trunk the fungus eats away at its branches compromising its strength and stability. Outwardly, the tree may show no signs of infection until a fallen limb is found to be hollow. This fact is most spectacularly demonstrated when a great limb is ripped from a living tree during a storm. All of the ancient trees so far mentioned have been recorded to have suffered this occurrence.

Dying for success: According to the ‘Woodland Trust’, the recognisably hollow trees are in the third and final stage of life. With their rotund shape and their major branches gone, they take on the familiar squat appearance and great cracks in their outer bark seductively lead to their hollow interiors. Who can resist the lure of entering the heart of a hollow oak? Certainly not the many thousands of visitors to the Major Oak. Little did Major Hayman Rooke know that from the moment he brought the Queen Oak to the attention of the general public, he was condemning the tree to a slow death. In the early 1970’s none of the experts could explain the fact that the Major Oak’s health had taken a sudden and dramatic turn for the worst and the tree was in fact dying. An urgent diagnosis of the cause was needed to save it. After a process of elimination it was found that the physical footfall of the thousands of visitors to the popular old oak had compacted the ground around the roots to such and extent that the tree was being starved of water (rainfall) and nutrients. A very quick and easy, practical solution was found to solve this deadly dilemma. In 1975 the Major Oak was fenced-off to the public and all access to the trees’ interior cavity forbidden. The ground around the tree was lightly ‘rotarvated’ and re-seeded with grass and all of its affected areas painted with a green anti-fungal paint. Astonishingly, the tree made an almost instant recovery, so much so that it has been found that the entrance hole to the interior has begun to close-up. When we look again at the Victorian print of the Cowthorpe Oak and the large crowd gathered around it, then I suggest that the trees’ demise in the 1950’s can be attributed, literally, to the footfall of its popularity.

Robin Hood’s Tree?: Over the years of their public popularity, all of the great oaks seemed to have competed for the number of people the interior space could hold and the often intriguing use that space could provide. Obviously, the larger the tree’s circumference the greater the potential hollow space within its trunk. The Major Oak has claimed to have once accommodated around 30 people whilst the Cowthorpe Oak upwards of 60. The hollow in the German oak tree has been turned into a chapel or prayer room dedicated to a local politicisation and diplomat Hans Wilhelm von Thummel who was buried beneath the roots of the tree in 1824. The Bowthorpe Oak’s hollow interior has played host to a table around which 13 guests have sat-around for tea.

It is however, the Major Oak which lays claim to the most famous use of its hollow trunk. The tree is infamously known as the hideout for Robin Hood and his outlaw band. Looking again at this popular story it can quite easily be proven as an exaggerated claim. If we except the trees age as being 1,000 years (+ or – 200 years) it gives us a date of around 1115 for the germination of the acorn. The most popular period for the setting of the Robin Hood legends is during the reign of King John 1199 – 1216. This means that the tree would have been around 84 years old at the beginning of John’s reign and 101 at the end of his reign. Squeezing the data a little by working on a later date for the Robin Hood legend and allowing for the tree to be a little older, we can come up with a figure of 300-400 years for the trees age at the time of Robin’s famous exploits in Sherwood Forest. Working on our previous calculations for judging the age of an oak from its girth, a tree of this age would have had a circumference of between 18′ and 20′. Even if the tree had been hollow at this age, there would not have been enough room inside to accommodate Robin and all his Merry Men. Perhaps it was just Robin and little John who hid inside the tree or more likely the whole story is a romantic invention, a Victorian myth. What ever the story’s origin, in the heart of every visitor, the Major Oak it will always be Robin’s secret hiding place.

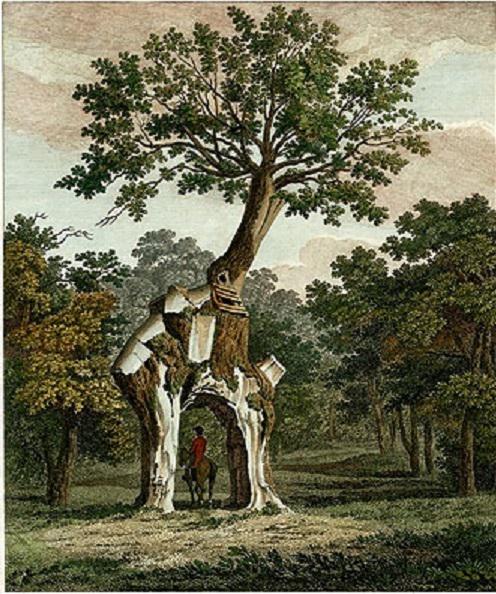

The Greendale Oak: Rooke in his account of the tree later to be known as the Major Oak wrote the line; “….the inside is decayed and hollowed out by age, which, with the assistance of the axe, might be made wide enough to admit a carriage through it”. In giving this rather alarming statement Rooke was making no idle jest, but rather a veiled recommendation of actually taking an axe to the tree. Writing in 1790, Rooke was addressing his comments to William Bentinck, 2nd Duke of Portland. He was in fact making a reference to the fate another mighty oak had suffered at the hands of William’s father, Henry Bentinck, 1st Duke of Portland. This tree, – a classic hollow oak, – known as the Greendale Oak, is said to have been at least 700 years old, over 30′ in circumference and around 54′ in height. In 1724 Henry Bentinck acted on a bet made at a dinner party, that he could drive a ‘carriage and four’ through the tree. To achieve this feat he had his woodsmen take their axe to the tree and cut an arch 6′ 3” wide and 10′ 3” high through its trunk. In cutting this arch it was clear that the surviving trunk would have been unable to support the major branches of the tree, and were therefore all remove. The wood however did not go to waste. One of Henry’s neighbours, ‘The Countess of Oxford’, being very fond of oak furniture, “….had several cabinets made of the branches and ornamented with inlaid representations of the oak”. The Greendale Oak became a popular visitors attraction and the most famous tree on the Duke’s estate. However, the savage attack by the Duke had shortened the trees natural life-span and by Victoria’s reign the tree was all but dead. Such was its bulk, the remains of its rotting carcass did not finally disappear until the mid 20th century.

I hope that the reader has enjoyed this look at just a few of the great oaks of Sherwood as much as I have. There are many more named oak trees in Sherwood Forest, all with interesting stories and I will be writing more on these at a latter date.