by Frank E Earp

A few weeks ago I visited Lincoln and took a guided walk through its ancient castle. Whilst on the castle walls I was impressed by the view across the roof tops of the city laid out between the castle and the cathedral. The crooked roof lines indicated timber-framed buildings masquerading beneath a shell of red brick as something more modern and their jumbled arrangement suggests a medieval town plan. I began to mentally compare the equivalent view from the walls of Nottingham Castle across the part of the city that would have been the old Norman town. The contrast is startling, for in Nottingham we have modern shops and officers, – many high-rise, – lining busy city streets. Gone is the original medieval town plan. Or has it? Dig a little deeper and we will find more than meets the naked eye.

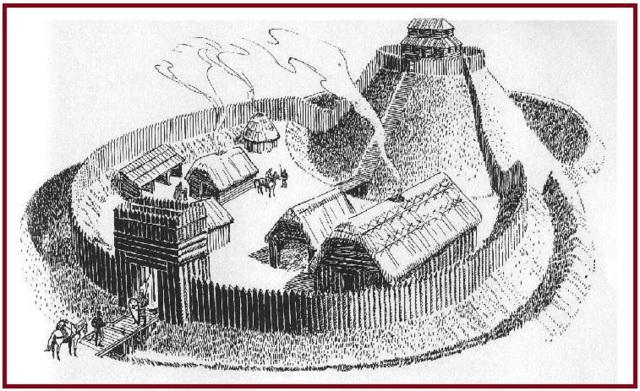

The First Castle: The origins of both Lincoln and Nottingham castles and their accompanying towns are strikingly similar. Both castles began life as Norman ‘mote and baily’ castles on strategic sites, built William Peverel on the orders of his father William the Conqueror around the year 1068. Both were set to dominate existing settlements; Lincoln, a Viking commercial and trading settlement and Nottingham, a Saxon Borough on a neighbouring hill around the Lace Market. The Normans were super-efficient at building these timber and earth castles to a standard design adapted to fit the chosen site. Many of these supposed temporary structures lasted hundreds of year before the most important castles were rebuilt in stone, which in the case of Nottingham Castle, was over 60 years later in the reign of Henry II. By this time a whole new Norman town had grown up with streets stretching north-east from the castle gates to the open space of the market which separated it from the old Saxon Borough. This market was to grow into one of the largest in the country. John Leland (Leyland), writing in the reign of Henry VIII, describes the market as; “….the Fairest without exception in all England.”

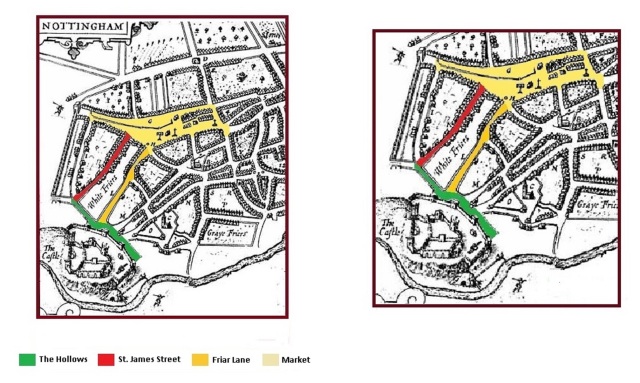

Norman Town: To create their new town, the Normans first established a number of parallel lanes linking the castle to the open space of the market. On the castle side, these ran at right angles from the ancient earthwork known as the ‘Hollows’, – which by this time had become a sunken road, – now part of Castle Road. This arrangement formed a grid pattern with roughly rectangular building plots of land between the lanes. By far the largest plot of land within the Norman town was that enclosed by St. James Street and Friar Lane which form its two long sides and The Hollows – now Castle Road and Beast Market Hill, – now Angel Row/Wheeler Gate, which formed the two short sides. As commercial properties and private houses began to be built on these vacant plots, a network of interconnecting alleys, side roads and yards grew up to form the new town.

Although not now recognisable on the ground, the Norman layout is still visible on a modern street plan of the City and the original lanes may still be walked; Mount Street, St, James Street, Friar Lane, Hounds Gate and Castle Gate. Only one of the five original Norman lanes retains its earliest name. Now St. James Street, from its creation to the present day, this road has been known by many variants of the same name: ‘Seynt Jame Lane’, ‘Seynt Jamgate’, ‘Sent Jacobs Lane’ and ‘Vicus Sancti Jacobi’. There is good reason for this to be the case. When the Normans first laid-out their new town, the land between the Castle and the market was not entirely empty. On a site now occupied by Bromely House Library, stood two buildings which played an important role in both the development of the area and indeed, Nottingham as a city. These were a Saxon manor house known as The Red Hall and its attendant private chapel dedicated to St. James. It wasn’t long before those using the new road closest too and leading past the chapel called it ‘Seynt Jame Lane’ (St. James Lane).

It was not military considerations alone which prompted England’s new king, – Duke William of Normandy, – to choose Nottingham for the site of a castle and new Norman town. By the year of the Conquest (1066) the little settlement of Snot’s, people, – ‘Snotingaham’, had grown into a thriving Saxon Borough, with an estimated population of 600 to 800 person. It had become an important ‘shire-town’ on the edge of a Royal forest with its own parish church, – St. Mary’s, – and a place that even minted its own coins. Leaving aside the importance and value of the Royal forest, Snotingaham, at this time returned annual tax revenue to the Crown of 75s. 7d. (£3. 15s. 7d.) with an additional 40s. (£2) from the two ‘moneyers’ (coin makers). To the west of Snotingaham was the manor and lands held for the Crown by the Saxon nobleman Earl Tostig. This manor contributed a further 3d. to the annual tax of the Borough, of which the King had 2d. and the Earl 1d.

A Saxon Manor: It is extremely likely that the Saxon great house known as the Red Hall, (mentioned in the first part of this article), was Tostig’s home. Like the lands and estates of every Saxon noble, Tostig’s manor had been forfeit at the time of the Conquest and was now in the hands of William Peverel. The convenience of having a manor house and chapel so close to the site of the castle was not overlooked by the Norman’s and the Red Hall was used by Peverel as both a dwelling and administration centre whilst the castle was under construction. Bounded on both sides by two of the new Norman lanes the Red Hall and the little chapel of St. James became the first significant buildings in the developing Norman town. The Domesday Book of 1086 records that Hugh Fitz Baldric had built 13 houses in the new township after he had taken the office of High Shire-Reeve (Sheriff) of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests in 1069.

The Chapel of St. James: Second only to the parish church of St Mary’s, the private manorial-chapel of St. James was the oldest Christian place of worship in Nottingham. There is evidence to show that the land around the chapel was still being used by inhabitants of the manor as a burial ground when the Normans ceased the property.

As time passed, a suitable residence and chapel were constructed within the confines of the castle wall and Red Hall was abandoned, slowly to decay into the pages of history. St. James chapel however survived and for a time became a ‘moot-hall’, – a kind of court-house, – of the Honour of Peverel. The various estates and manors own by feudal lords like Peverel, – who at this time held around 150 villages in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, – were collectively known as an Honour. Courts to settle legal disputes and disagreements between creditors and debtors and those seeking damages for trespass, were held in buildings known as moot halls.

St. James Chapel, which now became known as the Moothall, was accessible from both parallel lanes on either side. Having already given a name, ‘Seynt Jame Lane’ to the lane on the western side, that on the eastern side, (what is now Friar Lane), became known as ‘Moothall Gate’. The same building thus gave names to two of Nottingham’s streets. As a chapel it also gave its name to one of the City’s Wards, ‘Chapel Ward’, and to one of the gates in the medieval town walls, ‘Chapel Bar’.

Sometime between 1102 and 1108 William Peverel founded a Priory of the Cluniac Order in Lenton. The Moothall was given to the Prior and monks of Lenton and returned to its duties as a chapel and place of worship.

A reference to ‘the chapel of Nottingham’ in 1130-31 may well refer to St. James rather than the chapel within the Castle. The first reference to the chapel by name comes from documents of 1265-6, relating to ‘a certain chaplain at St. James’s outside the Castle’ who was given an annual stipend of 50s.

As villages and towns expanded and the need for new parish churches arose, it was customary wherever possible for private manorial chapels to receive parochial status. This does not appear to have been the case with the chapel of St. James. It would seem that when a new parish church was needed, St. James may not have been the only suitable chapel within the area. The foundation deeds of Lenton show that St. James was one of three private chapels given to the Priory along with the already established parish church of St. Marys; St. Nicholas and St. Peters being the other two. It was St. Nicholas on Castle Gate which was to become the first ‘new’ parish church in the mid-12th century, followed a few years later by St. Peters on Hounds Gate /St. Peters’ Street. This clearly demonstrates how rapidly the Norman town expanded.

The reason why St. James never developed into a parish church may be considered as both practical and political. Although it is referred to as a chapel with its own chaplain in 1265-6, the building continued to be used as a courthouse for the Peverel Court until 1328

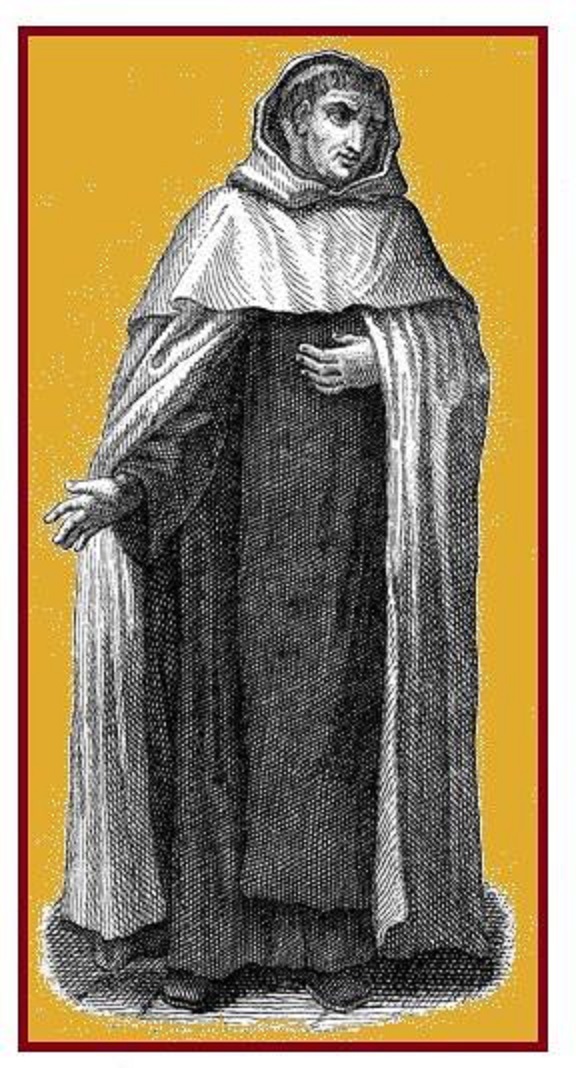

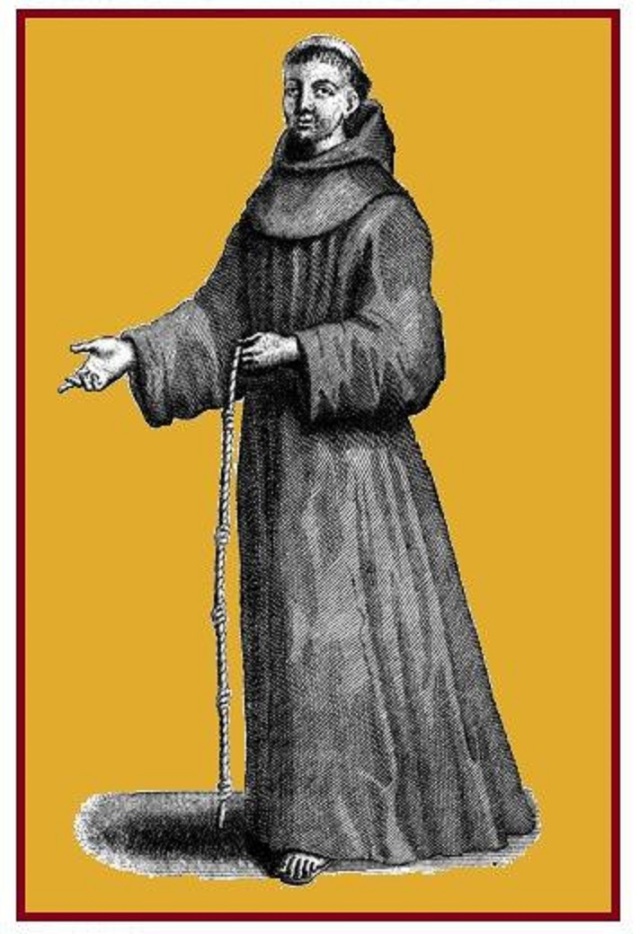

The coming of the ‘White Friars’: In 1272 a small group of Carmelite Friars, – also known as White Friars from the colour of their habit, – acquired a plot of land to establish a new Friary between St. James Lane and Moothall Gate. They also acquired a row of houses which bounded their property to the north along the side of Beast Market Hill. The Friary itself was a modest group of buildings for the Carmelites were an order bound to a vow of poverty and relying on begging and charity for a living. Very quickly after the establishment of the Friary, Moothall Gate became known as Friar Lane, – a name by which it is still known today. The Friars where to remain on this site for the next 250 years.

Having acquired this valuable central plot of land the Friars were presented with a problem, part of the site was already occupied by a building they did not own. Documents of the time state that they; ‘found their way barred by the decayed chapel of St. James’. For the next 44 years there followed a protracted ‘battle’ between the White Friars and the monks of Lenton for ownership of the chapel. In 1308 the Friars received permission from the Archbishop of York to dedicate an alter to the Virgin Mary, but this is likely to have been in one of their own buildings and not within the chapel.

Finally in 1316, King Edward II signed a deed which transferred to the Friary; ‘a certain plot of land, with the Chapel of St. James on the same plot, in the town of Nottingham, which he, (the King) had of the gift and grant of the Prior and Convent of Lenton, and a little lane leading to the chapel aforesaid, which chapel and lane adjoin the house of the said Prior and brethren’. However, having acquired the chapel, the Friars were still had the problem of the Peverel Court. Although with the deed of transfer, the Court had been moved to the county hall, someone had neglected to tell the kings bailiffs who were still trying to access the site some 12 years later. In 1328 we find record that the bailiffs had made the complaint that the Friars had; ‘enclosed the said chapel with a wall within their house, and so they impede the king’s bailiffs of the aforesaid fee, so that they cannot hold court in the aforesaid place’. The dispute was settled and the Friars were at last discharged of any duties relating to the court. This is the last time that the ancient chapel is called by the name of St. James, although the original Norman road continued to be referred to as St. James Lane or one of its many variants. From this time on the chapel becomes known as the Church of the Friary.

By the 12th century, Nottingham Castle had been completely rebuilt in stone and had become one of the finest royal residences and strongest fortresses in the Country. No wonder then it was the favourite residence of successive monarchs through to its destruction in the Civil War.

As the Castle grew and prospered, so did the new town at its foot. The little chapel of St. James, now the Church of the Friary, continued to play its role in the town’s life. It is extremely likely that the chapel played host to royalty from the time of the Conqueror himself. Records show that in August 1511, whilst staying at the Castle, Henry VIII attended divine service at the ‘Friar’s Church’ on three successive Sundays. Ordinary people too used the chapel and not always for the right reason. In 1393 we find that a man by the name of Henry de Whitley sought sanctuary from the law in the church after murdering his wife. The good Friars; ‘kept (him) to the church and (he) could not be taken.’ The will of Henry Fischer published in 1467 includes the request that he be buried; ‘In the church of the Friars Carmelite before the alter of St. Anne’.

Not all was peace and harmony in the Carmelite Friary. In 1441, a stone mason appropriately named John Mason, sued the White Friars for 2s 6d (half-a-crown); ‘….which the aforesaid prior owes and unjustly dertained from him, to wit, for his labour working on a stone wall’. Although the court ordered an inquiry, we do not know its outcome and weather John Mason received his money. In 1515 records show a reported attempted murder at the Friary. Seventeen years later in 1532 an actual murder took place, when the prior, Richard Sherwood, struck and killed one of his ‘brothers’ after a drunken quarrel.

The dispute between the Carmelite Friars and the monks of Lenton which had begun with the quarrel over the chapel seems to have rumbled on into the 16th century. At about the same time as Henry VIII visit, Dan Elingham, – ‘….a monke of Lenton, of St. Benedict’s order’, – was also visiting the Friary. He was dismayed to see a picture depicting John the Baptist dressed in Carmelite habit. In protest he wrote an open letter in Latin verse addressing the saint himself which began with the line; ‘Christa Baptist, this vesture does not become thee, he that clothed thee as a friar hath departed accursed’. An unknown White Friar replies in the same vain in a supposed answer from the Baptist, beginning with the line; ‘Elingham, thou liest, in metres both foolish and wonderful’. Concluding with the line; ‘I am a Carmelite by merit, but thou a Gehazite and false brother of Benedict, non benedictus, (not blessed)’.

After playing its part in the daily life of Nottingham for nearly 250 years, the end came for the Carmelite Friary on 5th February 1539 when the Friary and church were surrendered to the King’s Commissioners at the Dissolution of the Monasteries. By this time out of a thriving community, only the prior and six brothers remained in residence. With the friars gone, the abandoned ancient chapel and other friary building quickly fell into disrepair, a proses which was speeded up by the fact that the site was regularly plundered for stone and other building material. But this was not the end. The memory of the White Friars and the ancient chapel of St. James continued in the names of the adjoining roads, Friar Lane and St. James Street and the site of the friary, as we shall see, was reborn in a different guises.

Grey Friars: The White Friars were not the only friars to be seen within the town of Nottingham. Around 1230, shortly after their foundation Franciscan Friars, known as Grey Friars, acquired land on the south western edge of the Norman town. The area between Grey Friar Gate and Cannel Street is now occupied by the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre. The friary was originally built almost entirely of timber including oaks from Sherwood Forest, donated by King Henry III. The Friary church must have been a substantial building as records show the King donated 20 tiebeams for the construction of its roof. Around 1256, the church was rebuilt in stone taken from the Kings quarry in Nottingham. The nave and body of the church was completed in 1303, whilst the isles or side chapels were consecrated in 1310. The Grey Friars remained in Nottingham until 1539 when, just two days after the White Friars, the Warden (Prior) and seven friars surrendered the Friary surrendered to the King’s Commissioners

So far in this article we have seen how St. James Street developed from one of the original lanes of the new Norman town which grew-up in the shadow of the developing Nottingham Castle. We have also seen how, as a new road, its importance as one of the town’s main thoroughfares was guaranteed by two existing buildings, The Red Hall and the Chapel of St. James, – from which the street takes its name.

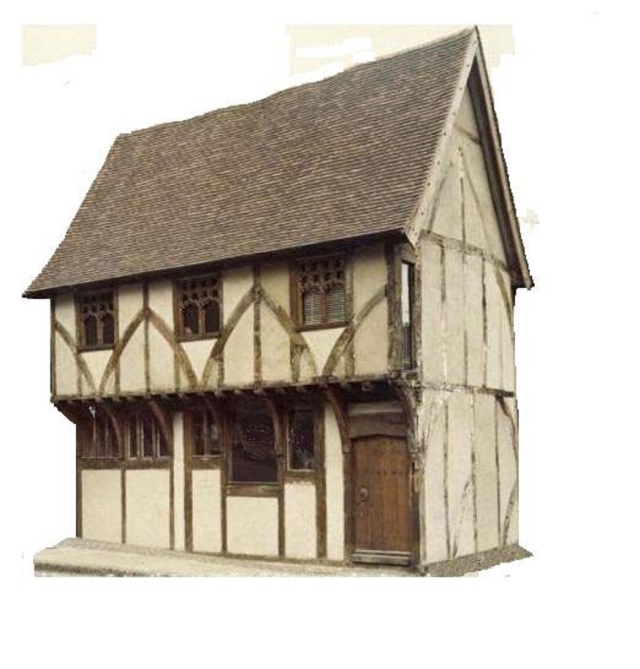

Medieval Thoroughfare: What of the street itself and the more humble commercial and private properties which lined its flanks? The Borough Records show that St. James Street developed in much the same way as any other medieval street Europe. Such streets were typified by half-timbered houses and tenements, (shops or business premises with second story accommodation above).

A network of yards, alleyways and passages connecting the original Norman lanes would have quickly developed. One such alley which became particularly notorious was Thoroughfare Yard, which connected St. James Street to the Market Square. This original passage survived well into the 1930’s.

The earliest reference to St. James Street by name comes from the Borough Records of 1315 and refers to a ‘messuage’ (a domestic dwelling and out buildings): ‘….in Vico Santi Jacobi next (to) the lane which leads towards the Berewordlane’. Berewordlane, now Mount Street, was another of the original Norman lanes. An entry in the Records for the year 1394 provides us with the name of one of St. James Street’s residence, John de Tannesley who acquired a tenement: ‘….in the direction of the Friars Carmelite on the eastern side (of the street) and the Redhall, on the western side’. We do not know what kind of business enterprise John operated from his tenement on St. James Street, but it must have been successful. We find that 16 years later, in 1410, the name John de Tannesley listed as Lord Mayor of Nottingham. A third reference in the Records of 1463 tells us of a grant of three cottages: ‘….lying together with gardens adjoining in Seynt Jamelane on the eastern side.’

With no proper sanitation the fact that overcrowded medieval streets could be dirty smelly places is attested too in our next reference. The Mickleton Jury of 1395 received a complaint that: ‘John de Blythe, fleshewer (butcher), blocks up Seynt Jame Lane with blood, entrails and issues, to the serious detriment of all the people passing’. Water supply for the residence and their domestic animals would have been supplied by both community and private wells of which there are around 300 listed in the town by the year 1700.

Dorothy Vernon’s House: As well as the half-timbered buildings there were more substantial stone buildings in St. James Street which were occupied by some of the towns more prominent citizens. By 1572, the Carmelite Friary lay in ruins and only the knave wall of St. James Chapel remained. However, the site, – known as Friar Yard, – appears to have remained undeveloped, for we find that in that year Sir John Manners (second son of Thomas Manners the 1st. Earl of Rutland), acquired the site together with an adjoining orchard and pastures. Incorporating the ruins Sir John built a substantial two storey ‘town house’. This house appears to have been somewhat unusual in that access to the second floor was via a spiral staircase in the outside front wall. Sir John’s wife was Dorothy Vernon daughter of Sir George Vernon of Haddon Hall in Derbyshire and the house quickly became known as Dorothy Vernon’s House. The story of Sir John Manners and his wife Dorothy Vernon is one for another article.

We have now concluded our brief history of St. James Street, from its Norman beginnings through to the end of the medieval period. However, the story does not end there. The streets role in the history and development of the City of Nottingham down to the present day will be the subject of a future article.